Sometimes bears like to use roads as much as people, giving new meaning to the “share the road” concept.

While enjoying a quiet bicycle ride on a remote road you surprise a large animal in the brush. A split second later, you realize the seriousness of the situation, because you didn’t surprise just any animal. You surprised a bear. Would you be prepared to respond appropriately? What can cyclists do to reduce risky bear encounters?

Some of North America’s most amazing cycling destinations are located in bear country—Alaska, the Rocky Mountains, the Appalachians, Cascades, and Sierra Nevada, and the Great Lakes region. I’ve lived, worked, and cycled extensively in bear country and I love it. I’ve commuted by bicycle at Yellowstone National Park. I’ve toured in the Appalachians, Rockies, and Cascades where bears are frequently seen. When I worked at Katmai National Park, Alaska, I had hundreds of encounters with brown bears, and I frequently saw them while riding the park’s Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes road. Each experience taught me to fear bears less and respect them more. Cyclists can safely enjoy riding in bear country, but there is risk involved. However, the risk is manageable with the right knowledge, prevention, and preparation.

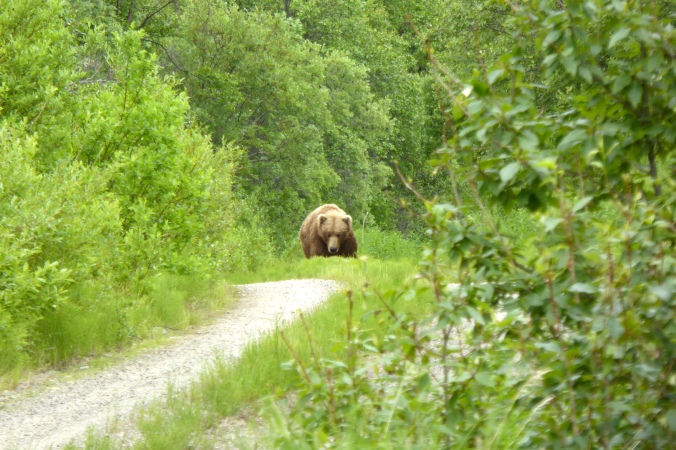

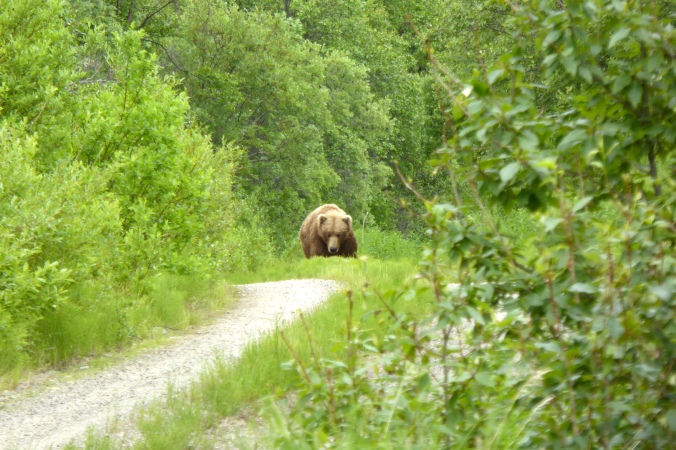

Cyclists need to be prepared for bear encounters. I found this bear walking toward me while I pedaled the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes road.

Cycling in bear country creates two main issues. First, bicycles are usually quiet and often travel at high speed increasing the possibility of surprising bears. Secondly, many touring cyclists prefer to camp, and while camping isn’t the problem, if you’re camping in bear country then the good campsite you found is often located in good bear habitat.

Warning noise is one of the easiest precautions to take in bear country. Given enough notice, many bears will avoid people. Noise is not a safety net though, just a preventative measure so you don’t surprise a bear. It must be made appropriately and for the right reasons. It’s especially useful in areas where visibility is limited, and it’s easy too. Use your voice or a loud bike bell. Those cheap bear bells may save your vocal chords for campfire songs later in the evening, but they aren’t nearly loud enough in most situations to adequately warn bears. More importantly, bears may not identify any bell’s sound with people. You need to make noise to warn bears of your approach and identify yourself as human. No bell is as effective as the human voice. It’s no fun to shout all day, nor is it an action that fits well in all settings, so vary the amount of warning noise as necessary.

If you need an excuse to slow down during a ride, bears can be it. Excessive speed was one of the main factors that led to a fatal mauling of a mountain biker in Montana. Ride cautiously where bears are frequently seen, avoid biking during hours when bears are less likely to expect encounters with people, and pay attention to your surroundings. On the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes road, a road that averages less than five vehicle trips a day in summer, I’m forced to ride slowly because too many bears use it to allow for a purely fitness ride. This is torturous for certain cyclists, myself included on occasion, but bears necessitate it. If I want to ride responsibly here, I must slow down.

Take the time to assess the terrain. Are you approaching the crest of a hill, a sharp bend, or is the road carved through thick brush? Will you be traveling through areas with food sources, like berries or salmon, that attract bears? This may seem like a mental burden that will cause a headache by the end of the day, but cyclists practice this risk assessment all of the time. While riding in traffic we identify and respond to unsafe situations routinely. Bears pose different challenges than cars, I realize, but trust your instincts. Slow down and give yourself time to use them.

This bear in Katmai was intent on using the road. To safely avoid a stressful encounter with him I stopped, picked my bike up, carried it off of the road and well into the forest to let the bear pass. Had I been traveling too fast, I would have risked surprising the bear at a very close range.

I let this black bear in North Cascades National Park know I was human by talking in a normal tone of voice. Once the bear realized I was human, he walked calmly into the forest.

Statistically speaking, groups of four or more people are very safe in bear country. So if the thought of encountering a bear alone is too intimidating, then join a group ride and stay close together. Group size is not effective if the group is spread so far apart that a bear only recognizes individual persons. Groups tend to be noisier and have lots of eyes to spot wildlife. Plus, during a bear encounter, a mass of humanity is intimidating to even the biggest bear.

With that being said, what should you do during a close encounter? Things can get complicated quickly and adrenaline will certainly rush, so prepare yourself mentally before you leave home. The key, according to Tammy Olson, a former wildlife biologist for Katmai National Park, “is to not behave in ways that are likely to be perceived as threatening when responding to a [defensive] bear at close range.”

How close is too close? The answer depends on a variety of factors (the presence of cubs, the vicinity of food like animal carcasses, the bear’s human-habituation level and disposition, surprise, and more). There are general recommendations to follow, but each bear is an individual and each situation is unique. A Yellowstone grizzly shouldn’t be treated like a Pennsylvania black bear. Talk with local officials about the general patterns of bear use and behavior in the area you plan on traveling through. Some areas, especially national parks, have regulations that define the minimum, legal distance to keep between yourself and a bear (50 yards at Katmai, 100 yards at Yellowstone, and 300 yards at Denali). These can be a useful, but not absolute, starting point to determine if you are too close. As a general rule, if you are altering the bear’s behavior, then you are too close.

Any time you find yourself in close quarters with a bear, stop riding and take a few seconds to assess the situation. Position your bicycle between you and the bear. As well as possibly adding a modicum of physical protection, the bike makes you look larger in a non-threatening way. Size matters in the bear world. This is why groups of people are generally safer in bear encounters than a lone person.

If you surprise a bear while bicycling, quickly assess the situation. What is the bear doing? Is it resting, feeding, approaching you, or showing signs of stress? Do you see or hear cubs? Is the bear vocalizing? Were you charged? Your behavior in these situations goes beyond the scope of this post, but what you see, hear, or think the bear is doing will influence your decision on how to react. (Please see the references at the end of the post for more information on bear behavior, identification, how to differentiate between defensive and predatory encounters, and the recommended responses.)

When you’re on a bike, you’re moving swiftly and you have less time to react than someone who is walking. This is more likely to provoke a charge from defensive bears, especially grizzly bears. If a bear charges you in a defensive, non-predatory situation, it is usually a bluff. Even so, this is a frightening experience. Hold your ground. Running or pedaling away may trigger the bear to chase you, and you can’t outrun a bear. Keep your bicycle with you if possible. Abandoning the bike, especially if there’s food in your panniers, can teach bears to approach people for another food reward.

Yelling at a defensive bear may provoke it further. Instead, talk to the bear calmly and back away slowly until the bear resumes its normal behavior (resting, feeding, traveling). Contact is rare, so only play dead if a bear makes physical contact with you. If it does, lie face down and cover your head and neck with your hands and arms. Remain still and quiet until the bear leaves the area. (Black bears attacks are very rare, but are much more likely to be predatory, so most bear behavior experts recommend you fight back if a black bear attacks.)

Sometimes you may see a bear before it is aware of you. If this happens, move away quietly the way you came and give the animal the room it needs. Find an appropriate place to observe it, where possible, and enjoy the moment. It’ll certainly be one you won’t forget.

Your goal should be to prevent close encounters. This is just as important when camping as it is when riding. At the end of a long day of bicycle touring, is there anything more satisfying than a beautiful campsite with a hot meal? Maybe not, but before you commit yourself to that wonderful campsite, take a few moments and search for signs of previous bear activity. Is there garbage scattered about from previous campers? Is the campsite near natural food sources that attract bears? Do you see fresh bear scat with human food or garbage in it? If so, consider moving on. You don’t want to risk a food conditioned bear coming into your camp at night.

Look for signs of bears like scat, tracks, and marking trees when you choose a campsite. Move on if the area seems to be frequently used by bears. The bear fur on this marking tree indicates plenty of bruins use the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes road.

Most problems with bears while camping can be avoided if bears aren’t attracted to your campsite in the first place. Outside of developed campgrounds, cook and eat well away from your sleeping area (at least 100 yards). This is a Leave No Trace principle everyone should follow, but it also disperses food odors away from your sleeping area.

Consider where and how you plan on preparing your food in the backcountry. Are hot meals important, or would cold dinners and snacks suffice? Eating cold meals and eliminating the need to cook is one easy way to substantially reduce food odors around your camp. There is less to clean and less garbage at the end of the day. If you choose to cook then consider meals that require little field preparation. Touring cyclists don’t normally carry and cook perishable, odorous items like bacon, but anything strongly scented or should be avoided.

Before you leave home, decide how you will store your food and other odorous items like soap and toothpaste. Bear resistant containers (BRCs) are the best and most portable way to keep bears from your food, and in some areas they are required. BRCs lack creases or hinges that allow bears to open them. Yes, they are heavy and bulky, but their effectiveness has been proven repeatedly and backpacking-style BRCs normally fit into a large, rear pannier. The most common alternative, hanging food in a tree, is time consuming and risky. Some bears, especially in the Sierra Nevada, have learned to ignore BRCs but specialize in stealing food hung in trees. Occasionally, developed campgrounds in high bear use areas provide food storage facilities as an alternative to BRCs, but many do not.

Lastly, some people prefer to carry a bear deterrent like bear spray (not self defense spray) or firearms. Neither firearms nor bear spray are 100% effective against bears. I carry bear spray since it is non-lethal, non-toxic, and easy to use. It is intended only for close encounters (generally 30 feet or less) on aggressive or attacking bears. This stuff is potent too, so be careful. I know enough people who have accidentally discharged their bear spray to know you don’t want it in your face or in your pants, as one unfortunate individual at Brooks Camp discovered. Wherever you choose to keep it, bear spray needs to be quickly accessible. When necessary, I carry bear spray in my bike’s handlebar bag. (Thankfully, I’ve never had to use mine.)

There are many bear deterrents, but the greatest of all is your brain. No matter what you do in bear country, where you ride, or what you see, there is no substitute for common sense. We empower ourselves with safe cycling practices in traffic, and we can do the same around bears. The scenario at the beginning of the article isn’t fiction. It happened to me, and it’ll probably happen again. Traveling in bear habitat requires responsibility. Sloppy habits and dirty campsites can endanger future visitors and the lives of bears.

I always look forward to bicycling in bear country, which is some of the most scenic and inspiring land imaginable. Knowledge of and respect for these animals can turn what would be a dangerous and fearful encounter into the highlight of the trip. Given the opportunity, humans, bears, and even bicycles can coexist.

More Bear Safety Information

You can never know too much about bears, but an action appropriate in one region may not be appropriate in another. Talk to local officials about what works and is expected in their area. There is also plenty of contradictory information available about bear safety available online. The information provided in the resources below generally follows the consensus of leading bear biologists and public land managers. Besides learning behavioral techniques that may keep you safe and give you peace of mind, learning about bears and their ecology is fascinating and can open up a world of wonder into their complex lives.

Websites:

Interagency Grizzly Bear Committee: The IGBC was established in 1983 to help ensure recovery of viable grizzly bear populations and their habitat in the Lower 48 states.

Leave No Trace: The seven guiding principles of LNT ethics not only reduce our impact on the outdoors, but also correlate to the best camping practices in bear country.

Yellowstone National Park Bear Safety Pages: These may be the most comprehensive bear safety pages on the web.

Get Bear Smart Society: This organization is dedicated to reducing conflicts between bears and people.

Literature:

Bear Attacks: Their Cause and Avoidance by Stephen Herrero: This is not your typical bear attack book. It written by a wildlife biologist who has statistically analyzed bear attacks across North America. It offers scientifically supported advice for travelers in bear country.

Backcountry Bear Basics: The Definitive Guide to Avoiding Unpleasant Encounters by Dave Smith: Although less academic than Bear Attacks, this is another readable, common sense look at bear identification, behavior, avoidance, safety, and it includes a brief section on mountain biking.

DVD:

Staying Safe in Bear Country: If there was just one resource you could choose to educate yourself on how to behave around grizzly and black bears, this video is near the top of the list. In a no-nonsense fashion, it clearly and accurately explains bear behavior and how people can minimize the chance of bear encounters and attacks. It also provides insightful footage of bear behavior that may be hard to visualize. A transcript is available too.

Bear cubs are apt to reflect mom’s mood. When she’s relaxed, they are relaxed. When mom is alert and stressed, her cubs are on edge. Cubs also take a keen interest in anything that their mother investigates. In this way, they learn much about what to eat, where to find food, and many other survival skills. In this way, mother bears are teachers. However, mother bears may teach their cubs behaviors that lead to conflict with humans.

Bear cubs are apt to reflect mom’s mood. When she’s relaxed, they are relaxed. When mom is alert and stressed, her cubs are on edge. Cubs also take a keen interest in anything that their mother investigates. In this way, they learn much about what to eat, where to find food, and many other survival skills. In this way, mother bears are teachers. However, mother bears may teach their cubs behaviors that lead to conflict with humans.