I want to write about people if you’ll indulge me. This is a topic that I almost never delve into, since I find the human realm less interesting than the non-human and the overall behavior of my fellow humans to be disappointing. (“Hey let’s start another war.” “Hey, I don’t care if the climate gets warmer.” “The suffering of others isn’t something that affects me.” etc.) I’ll touch on politics too, which I loathe. Not that I don’t remain engaged on issues that matter, and I always vote, but I find politics exhausting. The rhetoric from elected leaders and pundits is often disingenuous at best and too often purposefully deceitful. Our media industry, especially social media platforms, uses it to monetize outrage and divisiveness. I want to avoid adding to the cycle that got us here if that is at all possible.

But to be blunt, we’re experiencing a purge of national park staff that threatens the stability of parks.

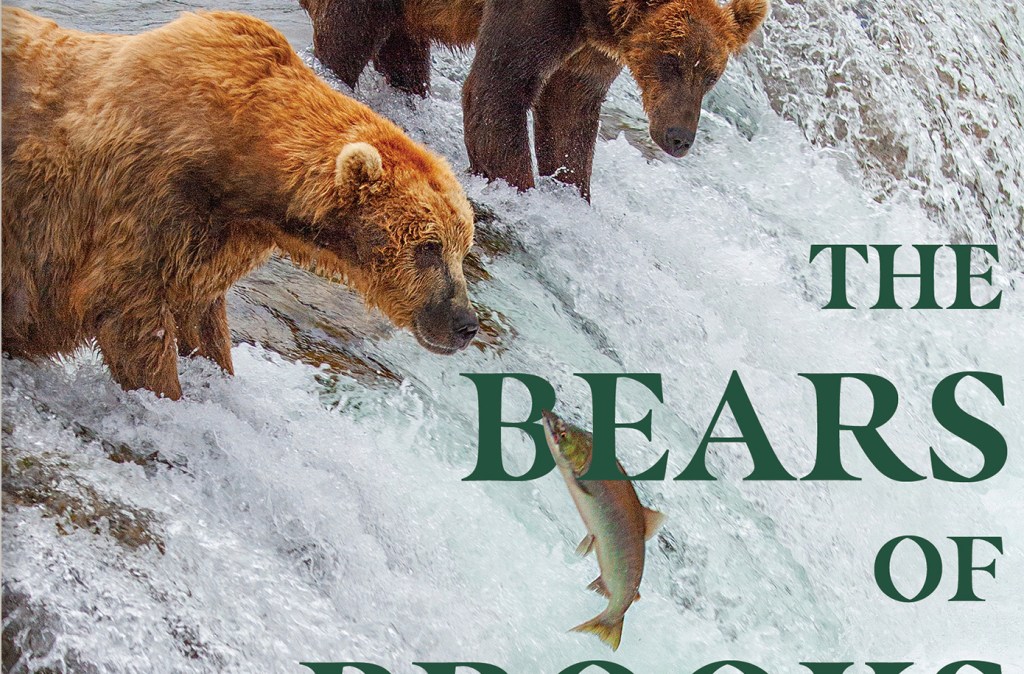

I worked in nine U.S. national parks, mostly as an interpretive ranger. Those are the rangers that lead programs, staff the visitor centers, and generally try to give people meaningful experiences. Although I no longer work for the National Park Service (NPS), I maintain close ties to parks across the country through family, friends, colleagues, the Katmai Conservancy, and my work for explore.org. Parks survive as places of significance through the support of the public and the work of NPS employees. The ability, however, of the NPS and other federal agencies to manage our public lands is facing a demanding, unnecessary challenge that will cause harm to these irreplaceable spaces.

By now, you’ve likely heard of the Fork in the Road, an attempt led by Elon Musk at the behest of the President to reduce the size of the U.S. federal workforce. Almost all federal civilian employees were offered a deferred resignation. Setting aside the confusion it sowed, its uncertain legality, and its ignorance of established regulations, the Fork was a not-so-subtle attempt to strong-arm employees into making a hasty decision about their careers. Those who didn’t take the offer were in no small way threatened that their jobs were not secure. “We cannot give you full assurance regarding the certainty of your position or agency,” as the Fork in the Road email stated in reference to those who do not accept the resignation offer.

The total number of employees who took the offer hasn’t been fully tallied, but it is likely that a few tens of thousands of people did resign across the entire federal government. As part of his justification, Musk argues that unelected bureaucrats have too much power, even as he fails to understand that he is now the quintessential example of an unelected, unaccountable bureaucrat. It is the Spiderman meme for real.

The Fork in the Road window is over, so to further reduce the federal workforce the administration is firing thousands of employees who were within a probationary period—a generally 1 – 2 year window that acts as an employment trial. Here is a good primer if you’re interested. During that time, your supervisor can decide whether your performance is acceptable. If it is, then great. Good work. Continue. We’re glad to have you. If it isn’t, then you could be fired due to poor performance. At least that is how it is supposed to work.

On February 14, about 1000 people lost their jobs in the National Park Service. That number could grow. Other land management agencies are targeted too such as the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (which manages wildlife refuges and endangered species), the U.S. Forest Service (which manages national forests and employs the nation’s largest wildfire fighting force), and the Bureau of Land Management (which manages large swaths of public lands that aren’t refuges, parks, or national forests).

The Fork in the Road and mass firings are different from Bill Clinton’s methods to reduce the federal workforce in the 1990s. Namely, Clinton’s plan was approved by Congress and implemented over three years. The current administration’s plan is not Congressionally approved. Its tactics are different too. Probationary employees are being fired en masse without consideration of the value of their job, the benefits they provide to the public, the skills they possess, or their work performance. The justification for the firings is nothing more than “not in the public interest” according to the emails they’ve received. That’s not a rational justification. It is pure ideological fervor that harms real people.

How does this affect the national park that I am most connected with, Katmai? Although I’m hopeful that many of Katmai’s probationary staff may be exempted from the firings, a loss of just a few staff members at Katmai will have a disproportionately large negative impact. Katmai’s year-round staff includes perhaps 30 people. In contrast, Yellowstone has closer to 750 year-round staff. Absorbing staffing cuts is generally easier for parks with a larger staff. Additionally, the administration has implemented a hiring freeze for most seasonal positions. Reports indicate that the NPS is allowed to hire 5,000 seasonal staff, but the park staff that I’ve talked to remain unsure if they will be able to hire all the staff they need. Five thousand seasonal employees is well short of the typical 7,000 to 8,000 that are usually hired annually.

The delay jeopardizes the ability of supervisors to hire, train, and get seasonal rangers in parks for the busiest time of the year. Katmai and most national parks cannot function properly without their seasonal workforce.

The NPS at Katmai employs about 12 seasonal interpretive rangers for Brooks Camp. These rangers provide mandatory bear safety talks, manage access to the extremely popular Brooks Falls wildlife-viewing platform, help in bear management situations, operate the visitor center, and lead programs. Most of the maintenance, law enforcement, and bear technicians (rangers that manage bear and human conflict) are also seasonal employees. The federal hiring freeze has created extraordinary uncertainty regarding the NPS’s ability to hire seasonal staff and get them ready to run Brooks Camp. The purge of probationary employees may also lead to the loss of some supervisors for the seasonal staff. Due to the administration’s actions, we’re likely at a breaking point where park staff will not be able to keep up with the workload that already exists.

For decades, the National Park Service has coped with too few employees for the work. Congress also saddles the NPS with perpetual budget deficits. I don’t think I ever had a supervisor in the nine parks that I worked at who wasn’t nearly or actually overwhelmed with work. Both Republicans and Democrats are at fault for this.

I wonder if you visited a park site if you would have noticed, because the NPS is really good at doing more with less. The NPS hides the stress and low morale felt by their employees and crumbling infrastructure behind smiling rangers wearing flat hats. Most people who aren’t employees don’t see the struggle to keep parks functional, the efforts made to ensure that people have good experiences despite ever increasing visitation, the knowledge and commitment necessary to study and protect ecosystems, or feel the day to day stress that comes with never being able to keep up. This spring and summer are likely to be some of the most challenging seasons that NPS employees have ever faced. People will still want to visit parks. They’ll still go to parks, but the NPS will lack the staff to provide for the best, safest experience.

The NPS shouldn’t hide the ramifications of mass firings and the seasonal job hiring freeze.

Layoffs don’t make the work of rangers go away. The public will see the results in the form of shuttered visitor centers, damage to park infrastructure, vandalism, increased emergency response time, wildlife harassment, poaching, road damage, campground closures, overflowing parking areas, and unclean bathrooms. Those things are difficult enough to address when parks are fully staffed. It is easier, cheaper, and more efficient to prevent those issues from occurring than to deal with the aftermath, just like it is easier to prevent infection through proper hygiene than to clean a wound of gangrene. Neglecting public lands now is a tax on the future.

“Where is the money supposed to come from?” you might ask. “After all, the national debt keeps going up and up and up.” If economics matter to you, then please consider that national park tourism generates more revenue than it costs the parks to operate and supports hundreds of thousands of jobs nationwide outside of the NPS. The requested NPS budget in 2023, for example, was $4.75 billion, while the 2023 economic output of national parks was more than $55 billion. For every dollar invested in national parks, taxpayers get much more in return. I bet our Congress and President find money for more bombs in the midst of all this. There always seems to be money for more bombs. They might also fight to provide more tax breaks for the ultra-wealthy because the rich always seem to need more money to feed their greed. So let’s not pretend that firing hardworking and dedicated NPS employees is a true means to reduce debt or taxpayer burden or make government more efficient. It is driven by an ideological agenda.

Our public lands are the nation’s most cherished spaces. The tech billionaires and politicians want you to think that it is GDP, stock values, Walmart, Amazon, Tesla, and Facebook. In reality it is our shared democratic spaces such as parks, wildlife refuges, and national forests.

Most everyone can agree that the U.S. government can spend its money more wisely and efficiently. I favor that. I would question the rationality of anyone who thinks otherwise. Scapegoating federal employees as the problem, however, isn’t a solution. The goal of elected leaders should be to make government work better, not break it. But here we are.

If you’ve read this far, you’re likely a Brooks River bearcam watcher. It remains to be seen how firings will ultimately affect the operation of Brooks Camp this summer. Yet more people than ever before visited Brooks Camp in 2024 (about 19,000 according to park statistics provided to me). Even if visitation declines overall, the nature of the Brooks Camp experience means that it will remain an intensely managed place. Katmai will be especially challenged to ensure that bears and people are safe at the park’s most visited site. The bearcams on explore.org will not be affected, thankfully, but that is of little solace to me knowing that friends and colleagues may be fired solely for ideology. It is not ethical. It is not in the best interest of the taxpayer. It is cruel.

Finally, there’s been a lot of talk of loyalty from the administration. Federal workers need to be loyal, etc. Loyalty for NPS employees doesn’t mean capitulating to a presidential administration’s ideology, which comes and goes on the will of voters. Loyalty for NPS employees means staying loyal to the NPS mission and purpose, which was established by Congressional law in 1916. It is in the U.S. Code. NPS employees cannot escape it nor should they.

The NPS mission is somewhat contradictory and often frustrating to fulfill. I lived the contradiction as a ranger when struggling to determine how to best provide for enjoyment without impairing the things that make parks special. Ensuring that parks meet their Congressional mandates is where the loyalty of NPS employees truly rests. That’s how it is supposed to work. It safeguards parks against the whims of politicians.

I would still consider the current methods to purge the government workforce as wrong even if it were applied to areas of government that I disagree with on principle. Don’t hand the reins of power to an unelected billionaire bureaucrat. Consider how you’d react if you are on the other end of overreaching, unchecked presidential powers in the future. If you don’t like the way that the NPS operates, then work through Congress to change it.

If this is an issue that matters to you and you haven’t contacted your congressional representatives about it, please do. Calling might be better than writing, but this template has some good starting points to communicate. There are a lot of other reasons to write to them as well like their efforts to erase the existence of Trans people. We can get through this but not without holding elected and unelected people accountable, and not without reining in the powers of the presidency.