Consider the plight of the northern acorn barnacle. They begin life as planktonic larvae drifting in the vast ocean, motile yet vulnerable. If one survives its many instar stages, it then seeks a more permanent home. The barnacle settles out of the water column and glues their antennae to a rock or other suitable location where they metamorphose into the shelly animal that we’re most familiar with. There’s no going back at this stage of life. The barnacle has become forever sessile with a head cemented to rock and legs filtering food from the water.

Many barnacle larvae never get the opportunity to make a permanent home. Predators or some other hazard culls their numbers. They must be choosy in their settled life too. A forever home needs to be close to other barnacles, since mating takes place between closely neighboring barnacles.

Once secured to the rock, flood tides carry life-sustaining nutrients as well as predators like sea stars and dog whelks. Ebb tides expose the barnacle to suffocating air, potential dehydration, intense summer sun, and winter’s freezing temperatures.

Still, their adaptations provide for success despite the risks. I described it as a plight earlier, and although their journey is filled with uncertainty, perhaps I am being unfair to them. Acorn barnacles are common in North Atlantic intertidal zones. Their shell resists the forces that work against them. The acorn barnacle is a tough critter built for enduring uncertainty and extremes of its intertidal habitat.

Tidal zones and the creatures that make a living amongst the habitat’s extremes have always fascinated me. I’m not aware of any habitat that changes its mood and appearance as much as the intertidal, which is why I found myself earlier this year at Canada’s Fundy National Park, wondering about barnacles and power of the ocean as I watched the biggest tides in the world.

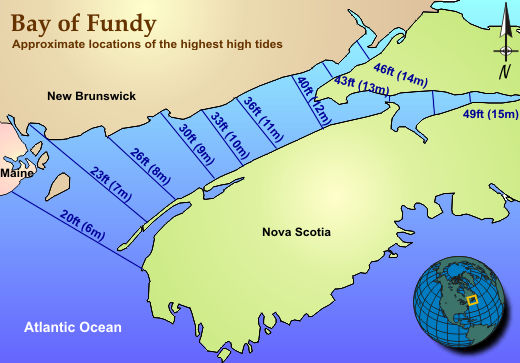

My first opportunity to really pay attention to tides was at Assateague Island when, fresh out of college, I spent two summers working at the national seashore. Assateague’s modest three-foot tides never became life threatening (not even when I purposefully got myself stuck in quicksand up to my waist). When the tide got inconvenient, I could mosey away. An incoming Fundy tide demands attention, however. Twelve meters—forty feet—of water rise twice a day along Fundy National Park’s headlands. Places farther north and east can experience even larger tides, perhaps 16 meters or greater in height.

I wanted to watch the tides transition fully from low to high, so I planned the trip to coincide with mid morning low tides and mid afternoon high tides. On my first full day in the park, I set up a chair on the Alma Beach about 30 minutes before the predicted nadir of low tide and walked down to the water’s edge.

The outgoing tide opened access to vast mud and sandy flats, which are extraordinarily tempting to explore. After all, who doesn’t see a mile of mud in front on them and not want to be out in it? I had to remain cautious, though. I lacked knowledge of the shorelines topography and the water’s nuanced interactions with it. I worked to always keep an avenue of escape available.

An accident of geography allows Fundy tides to become so large. The bay’s shape accentuates tidal forces. According to NOAA,

“Liquid in a tank, or in this case a basin, will flow back and forth in a characteristic “oscillation” period and, if conditions are right, will oscillate rhythmically. In essence, a standing wave develops. The natural period of oscillation in the Bay of Fundy is approximately 12 hours, which is also about the same length of time for one tidal oscillation (a high/low tide cycle). This coinciding of the tide cycle and the bay oscillation period results in the much larger tidal ranges observed in the bay.”

The shift from ebb to flood tide was easy to see at the water’s edge. Unlike the in-and-out rhythm of waves on a more exposed seashore with smaller tides, the water on the Fundy tide slapped upward with each successive wave once the tide turned.

During a low tide cycle the next day, I walked to the exposed headlands at the Point Wolf River estuary. The shoreline showed all the signs of extreme tides, of course, but I still found the height of the tides hard to fathom. I stood far beneath the lower limit of the acorn barnacles and the rockweeds hanging limp in the dry air. The twisting wrack line from the previous high tide was out of sight on the cliff above. I saw evidence of powerful winter storms that uprooted trees and eroded soils approximately 60 feet above me.

Within the estuary, the water rolled uphill at the pace of a slow walk.

Tides remain a force that humans cannot control. Like the barnacle, we can only adapt to them. In Alma, the small New Brunswick town adjacent to the national park, lobster boats could leave or enter the harbor only at certain tide levels.

Barnacles seem get on with the business of life no matter the phase of the tide. Yet I can’t help consider what their lives must be like secured to a rock for their entire adult lives, living in a habitat changing at a pace that even a lowly human can see. For them, the intertidal might symbolize perfection.

Very interesting article Mike—well presented and informative. I have been in places with high tide ranges, i.e. Cook Inlet, AK, but not as extreme as what you described/showed in Fundy Bay. Pretty amazing how quickly the high tide comes in!!

Thanks as always for your interesting posts.

LikeLike

The tides in Cook Inlet are amazing too, especially the bore tide in Turnagain Arm.

LikeLike

Excellent post. (Never really thought about the life of barnacles before.)

RE: Bay of Fundy tides: I can recall more than one high school geology field trip where we had to scramble to keep ahead of the incoming high tide after getting distracted fossil-hunting on the Nova Scotia side of the bay (way back when there were no controls on what you could take from the area, be it fossils or chunks of amethyst).

LikeLike

I can imagine the scene. I also visited some amazing fossil localities on the New Brunswick coast (just to admire, not collect of course). Next time I go back, I want to have a better plan in place to admire more fossil beds.

LikeLike