There’s a walk I’ve been eager to follow since reading about it in A Guide to the Geology of Baxter State Park and Katahdin. So on a warm day in early September, I found myself meandering downstream along the South Branch of Trout Brook.

I was fortunate to be there at that time of year. Water levels were low, which made for easy walking. Water temperatures were cool, which allowed my wet feet to buffer the heat of the day. Importantly, biting insects were few, which permitted me to enjoy the scenery without taking extraordinary measures to protect exposed skin.

A hike down the South Branch is intriguing because stream erosion exposes a series of rock formations that reveal a 400 million year-old story. In it we find the violence of long extinct volcanoes as well as the marvel of the first plants to colonize land on Earth. It is a story of immense time and change.

Maine in the early Devonian Period, about 400 million years ago, would be wholly unrecognizable. The landmasses that would become Maine were located south of the equator. Extensive volcanism scalded the Katahdin region. Terrestrial vertebrates weren’t yet a thing. Dinosaurs were still about 150 million years into the future. Perhaps the oceans would be the only similarity we could recognize.

To explore this age of Earth’s past, I began at South Branch Falls which was empty of people when I arrived in mid-morning. It is an appealing swim spot with shoots and pools carved into Traveler Rhyolite, a rock formation created by ash fall and pyroclastic flows that may have filled a volcanic caldera about 407 million years ago.

In contrast, nearby Katahdin, Maine’s tallest peak, in the southern portion of Baxter State Park is composed of granites.

Despite their differences in appearance and texture, rhyolite and granite are chemical equivalents. Both are formed from silica-rich magma. The difference is a product of time and location. Rhyolite is a volcanic rock formed from viscous lava. Because of its high viscosity it tends to erupt explosively—think Plinian type eruptions such as Krakatoa in 1883. Granite, though, forms underground when silica-rich magma is given the opportunity to crystalize over millions of years. According to the aforementioned Guide to the Geology of Baxter State Park and Katahdin, mineralogical analysis confirms the relatedness of the Katahdin Granite and the Traveler Rhyolite. They both date to about the same age too, although the rhyolite must be younger since it rests on top of the granite and there’s no evidence that the granite intruded into the rhyolite. Katahdin’s granite, therefore, is the solidified core of a magma chamber that fed the eruptions resulting in the Traveler Rhyolite.

The nearest modern analog to the Traveler Rhyolite that I have seen is the pyroclastic flows of the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes in Katmai National Park, but that was result of a single, 60-hour eruption. While Traveler Rhyolite is not a widespread rock formation currently it may have once covered a much more extensive area. It is also voluminous where it remains, perhaps accumulating to a total depth of 10,000 feet (3,000 meters) from the successive accumulations of an unknown number of eruptions. The enormity of the eruptions that created the Traveler Rhyolite is difficult to imagine. The serenity of a quiet morning at South Branch Falls fails to capture the violence of the events that created the bedrock here.

I left the falls to walk downstream before anyone arrived to wonder why I was putting my face so close to the bedrock (I’m not much of a conversationalist when out in public) but not before stopping slightly downstream to watch fish…

…and to identify a species of willow I had not seen before.

Much of the rock in Maine has been subject to deformation by plate tectonics and mountain building processes. Occurring between the Late Silurian and Devonian, the Acadian Orogeny saw the convergence of crustal terranes (essentially fragments of crustal plates with different geologic histories) as well as the creation of volcanic arcs and the folding metamorphism that accompanies tectonic collisions. Part of modern Maine and Atlantic Canada belongs to Avalonia, a crustal terrane that is also found in Europe from Ireland to Poland. Still more bedrock was formed under the Iapetus Ocean, an ancestral Atlantic that closed in the Paleozoic. Imagine the mess of geology which would be created by the collision of Sumatra, New Guinea, and Borneo into mainland southeast Asia by future tectonic movement. Something like that happened in the area we now call the Northeast U.S. and Atlantic Canada about 400 million years ago. The geology, as you can infer, gets complicated quickly.

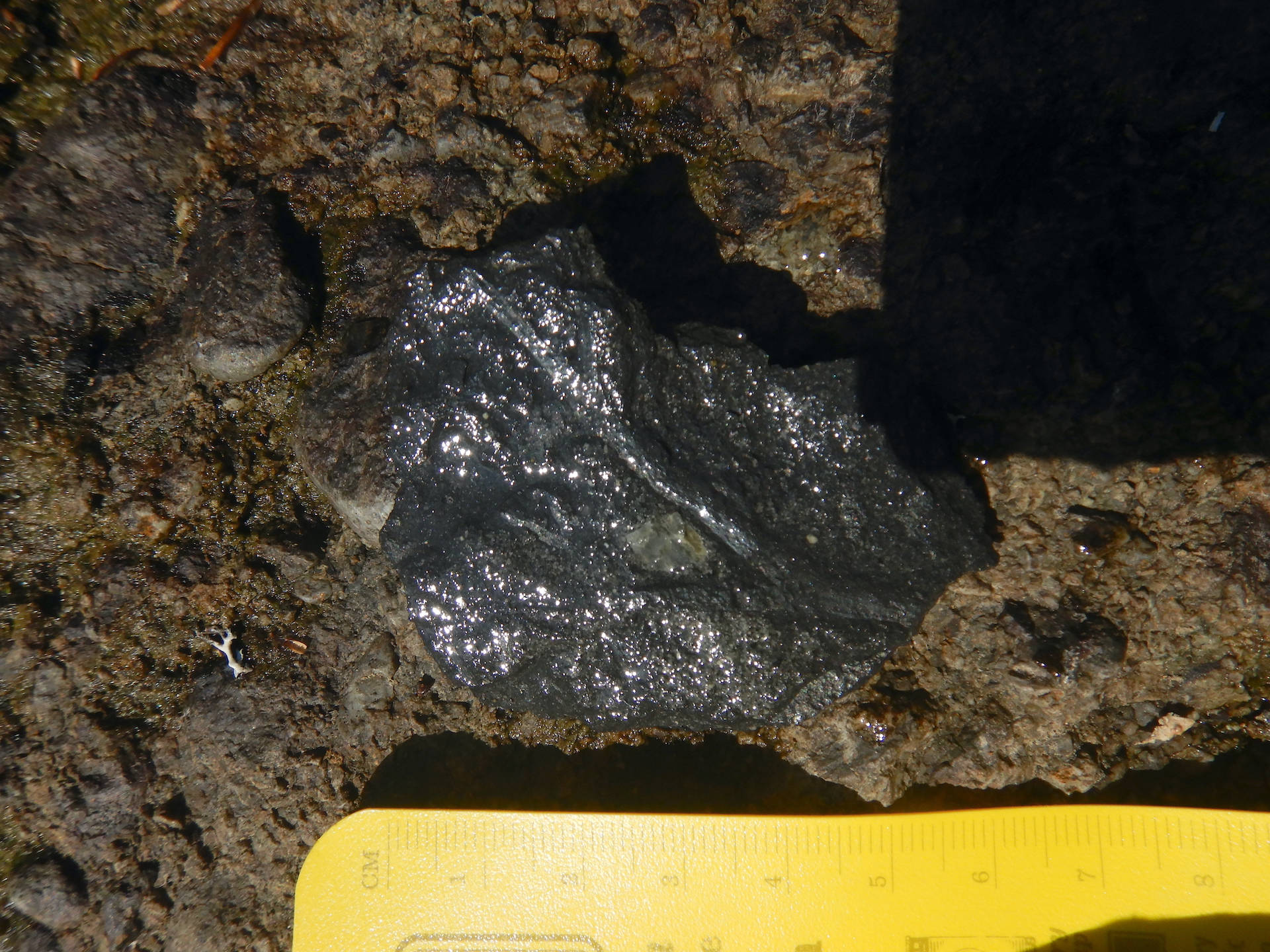

So owing to the forces formerly at work here, it is uncommon to find unaltered sedimentary rocks in this neighborhood. They are usually tilted, folded, and baked. Yet, only few hundred meters downstream of the South Branch falls the bedrock changed and we’re provided with a rare example to the contrary.

The Gifford Conglomerate is a section of the larger Trout Valley Formation, a collection of younger, Devonian-aged sedimentary rocks overtopping the Traveler Rhyolite. This is reportedly one of the few places in Maine where sedimentary rocks formed post Acadian Orogeny and haven’t been extensively altered even though they did experience some metamorphic change. With its rusty cliffs and shallow grottos, this section of stream was also particularly beautiful.

As I continued downstream, the conglomerate disappeared under rocks with a finer consistency. As these sediments accumulated the plants growing among them seized a revolutionary opportunity.

The Trout Valley Formation contains some of Earth’s oldest terrestrial plant fossils. At first, finding the fossils was a challenge. I wasn’t sure exactly where to look, but once I developed an eye for them then they popped into view.

Forests of the late Devonian included tree-sized plants, but that was still several million years into the future. The plants found in the Trout Valley Formation had only just begun the colonization of dry land and they remained small in stature. One Psilophyton species reached a foot or two (a few decimeters) in height. Another Psilophyton had dainty 3 millimeter-wide stems. Kaulangiophyton akantha (don’t ask me how to pronounce that) had almost centimeter-wide stems with irregularly spaced spines. Pertica quadrifaria is the tallest known plant of its time. It grew to be about 10 feet (~3 meters) tall with stems about 0.6 inches (1.5 cm) in diameter. They were perhaps fragile as well. Their fossils are often highly fragmented.

Sidenote: I hesitated to include any mention of fossils because certain people are dicks and steal them. But I chose to include them anyway because they are frequently mentioned in the published book I used to guide me. The state park also has a publication noting some fossil locations online. Athough collecting is prohibited in Baxter State Park, there is still a risk someone will read this and steal fossils. Please don’t be that guy. Leave the fossils where they are for others to enjoy and study.

So here are 400 million year-old plant fossils comprising few to several species found in finely grained sediments. What might this tell us about the habitat they lived in? The authors of one of the first papers to formally describe the fossils, published in 1977, stated, “The number of plants found at a single site is very small, usually only one species, occasionally two or three at most. There seems to be a valid comparison with present-day marshland vegetation along the New England coast where the number of species is relatively small over much of the area with scattered peripheral patches of other species that occupy smaller niches in the landscape.” When I read that I immediately thought, “Hmm…sounds like a salt marsh.”

Salt marshes are harsh environments for plants. For most species, it is an uninhabitable space. Vegetation must be able to survive flooding by tides, oxygen-poor soils, and high salinity. But for the plants that possess the physiological adaptations to cope with the challenges, the salt marsh becomes a richly productive environment.

On the east coast of the United States, salt marshes exist in the wetland transition zone between the sea and land. Salt marsh or smooth cordgrass (Spartina alterniflora) dominates the low marsh, the area flooded by tides each day. It grows in sand, clays, and mud. It can tolerate salinities that are double that of sea water by excluding salts from entering its roots, sequestering of sodium in its tissues, and secreting excess salt through its leaves. It counters a lack of oxygen in the soil with stems and roots connected through air pockets. No other plant in its native range copes as well with the salt, flooding, and disturbances that cordgrass experiences.

While smooth cordgrass dominates the low marsh, salt meadow hay (Spartina patens) outcompetes it in places above the average high tide line. Salicornia, a tasty edible, finds space in salt pans where conditions can be too harsh for even the Spartina grasses. When I learned to recognize the dominant plants of salt marshes while working at Assateague Island, I could use that information to note at a glance the approximate average high tide and the driest, saltiest places in the marshes. In east coast salt marshes, the few thriving species grow in habitats that differ in salinity and tide exposure.

Might the first plants that took to the land in the Devonian have created habitats that resembled salt marshes? I do not possess the ability, imagination, or knowledge to adequately envision those environments. But that won’t stop me from trying. There were no grasses or flowering plants or even seed-bearing plants in the Devonian so the scene was different. Even so, perhaps a series of extensive mudflats and braided streams flowed into the sea on the edge of an eroding volcano. Maybe some of the now fossilized species were best adapted for habitats closer to fresh water. Others could have preferred spaces inundated by tides. Disturbance and competition may have partitioned them into habitats perfect for some and harsh for others.

After continuing downstream where most of the Trout Valley Formation became hidden under a veneer of glacial till and not far from the South Branch’s confluence with the main stem of Trout Brook, I paused to admire a large sugar maple.

Perhaps 75 feet tall, its broad crown of leaves included the first hints of fall color. The tree was a fine representative of its species. A world without sugar maples would be a poor one, I think, and the humble fossils I examined upstream represent a beachhead for land plants to eventually become beings as magnificent as maples. In the Devonian, terrestrial plants began to stabilize landscapes from erosion, create soils rich in nutrients, and provide food for arthropods and vertebrates. It might’ve been the first time in Earth’s history when an organism with my oxygen needs could have breathed the air and survived.

Each fossil I found was a plant that grew for months or years. It died during a specific point in time at specific place. In contrast to the collective millions of years preserved in the rocks and the hundreds of millions of years of evolution represented by the maple tree and me, each fossil represents single moments of life and death. They are, paradoxically, the past and the present and the future.

Although this is an ancient story, I’m not sure “ancient” is an appropriate adjective for it. In my mind, the word implies a connection to human antiquity, while this story of change is a chapter of Deep Time. It is part of the arc of Earth history before humanity’s evolved ability to conceive of it. We can, though, draw a metaphoric line between the volcanoes that once blanketed the area under thousands of feet of ash to the plants which grew in tidal marshes to the forests that now bath my lunges in oxygen. I might live in a different world, but my existence remains rooted in the events preserved in these rocks.