Before I began training for a marathon last winter, my running efforts were casual and rarely exceeded six miles. I ran when I felt I needed to maintain a modicum of fitness and when the weather was too poor for the other activities that I typically find more enjoyable such as bicycling or long hikes. I’ve walked more than 20 miles in a day at least twice and ridden a few century rides on a fully loaded touring bicycle, but—as I discovered—running a marathon is not those things.

Reactions of friends and family toward news of my marathon goal were two-pronged. First, I received a quizzical you-might-regret-it look. The conversation then shifted to the inevitable question, “Which marathon?” My own, was my simple reply. The thought of running an organized marathon seemed much too stressful. What if I wasn’t feeling well the day of the race? What if I didn’t sleep well the night before? What if I didn’t want to be around other people? Running on my own time at a place I chose solved those dilemmas.

That’s how I found myself in April 2025 running the Northern Maine Mike Fitz Memorial Fun Run 42K Act-like-a-tough-guy Marathon Classic. By using quiet roads during Maine’s infamous springtime mud season, my marathon became a solo event where I avoided anyone else on foot. It also gave me a lot of time to think.

On training runs I often wondered about other organisms that regularly achieve amazing feats of endurance. Who could I compare my efforts to? After feasting all summer in Alaska, humpback whales migrate to Hawaii or the Pacific coast of Mexico. Bar-tailed godwits fly for eight days without stopping between Alaska and New Zealand. I’m on the other side of the continent, however. A local connection would be more appropriate. Wood frogs endure winter frozen like an ice cube in the leaf litter of my woods. But that’s a slow endurance, maybe even best considered a tolerance for challenging conditions. Black bear hibernation wouldn’t be an apt comparison either, since that process revolves around energy conservation and limited movement. White-tailed deer make local migrations to wintering yards with thinner snowpack like under a dense canopy of conifers, but that is a bit of a browse-as-you-go strategy and may not cover long distances. What about a migrating songbird such as a thrush, warbler, wren, or vireo? They are small-bodied, energetic, warm-blooded, and achieve amazing migrations. There are many I could’ve compared my marathon with. My area of Maine hosts at least 22 species of wood warblers. All of them migrate south for the winter. One warbler makes the journey unlike any other, however.

Dear Blackpoll Warbler,

What do you feel when you leave Maine in October? What forces draw you south to fly non-stop over the Atlantic to the north coast of South America? Are you nervous or anxious to begin? Is it anything like wanderlust or it is more powerful? Do you feel relief when you arrive? Do you feel hunger along the way? If so, does it feel different than normal?

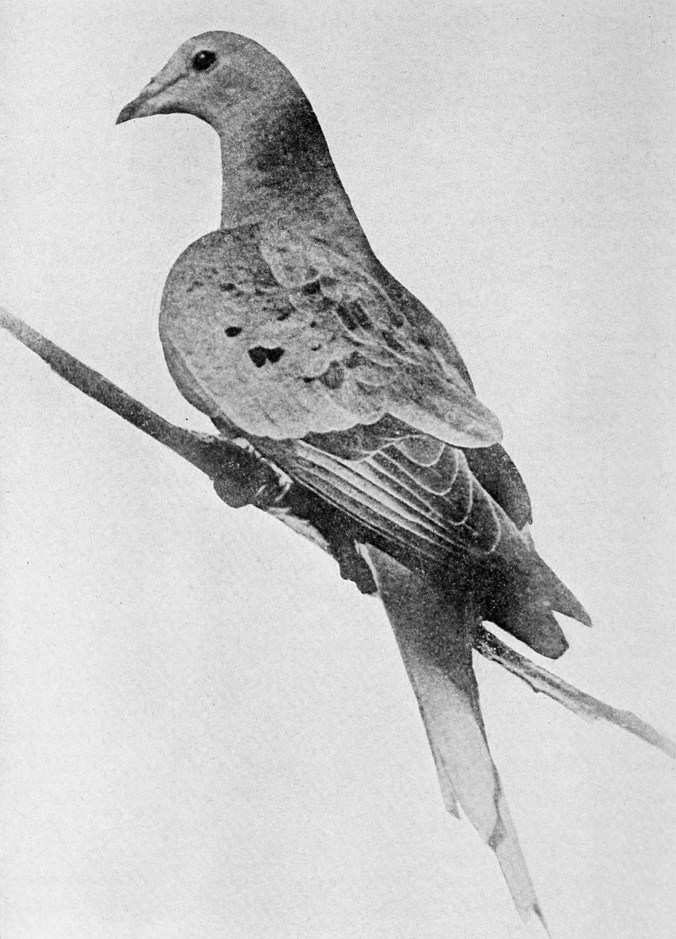

Blackpoll warblers (Setophaga striata) are smaller-than-sparrow-sized, primarily insectivorous birds. Summers are spent nesting in coniferous forests of northern North America from Alaska to Nova Scotia. In my area, I find them among dense stands of spruce and fir trees, especially on mountains like Mount Chase, but they also breed at sea level in conifer-dominated forests along Eastern Maine’s coastline where the ocean temperatures chill summer’s heat.

Blackpolls are part of an explosion of migratory songbirds that breed in Maine every summer, and after a long quiet winter I long to hear the forests filled with their shouts again. Unlike some of the bouncier and louder songs of sparrows, other warblers, and ruby-crowned kinglets, the blackpoll’s song is easy to miss. Its frequency range is among the highest known among birds. Whenever I hear it, I know I’ve entered a boreal place.

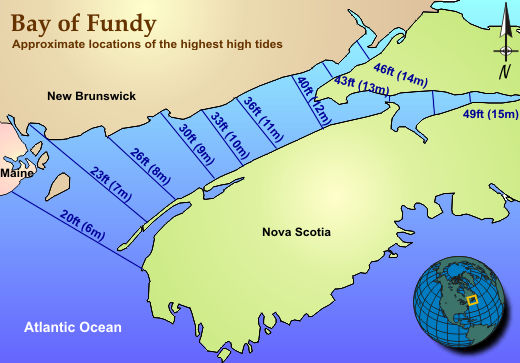

Their migration routes vary, although their month-long northward journey in spring typically utilizes many overland stopovers from South America across the Caribbean to Florida and the mainland U.S. The southward migration is when the birds express their greatest endurance. Blackpolls in Maine and Nova Scotia frequently launch due south in early fall on a route that takes them directly over the Atlantic Ocean. They follow prevailing winds out past the island of Bermuda until trade winds bring them back toward the Caribbean shore of South America. The three day trip is one of the longest, non-stop overwater flights yet known among migratory songbirds.

Humans are well adapted for running. Sweat shunts body heat to the skin where evaporation carries it away to prevent overheating. Our upright posture offers an efficient stride and improves our line of sight, all the while freeing our hands to carry tools and other objects. In contrast, long-distance running is hard for lots of other animals, so their running efforts are usually measured to take advantage of their particular suite of adaptations. The white-tailed deer, moose, and black bears that I share my forest with can easily outpace me in a 100 or 1000 meter dash (among mammals, humans are not great sprinters), but those species also overheat quickly, especially on a warm day, while a person could still be trotting along, sweating, yes, but also clearheaded enough to consider tactics and communicate with other people.

It would’ve been a mistake to attempt my marathon without training, so I started building running endurance about 16 weeks before I ran the full length. Following the recommendations outlined in The Non-Runner’s Marathon Trainer, I ran three times per week. The two shorter runs were of equal length and the long run was about 1/3 longer. Total mileage increased each week. I had to get used to eating and drinking during the longer runs and pay attention to my stride to prevent injury from repetition of movement.

The blackpoll prepares for migration in his own way too. Cues from day length calibrate his internal clock with the season so he knows to leave at the optimal time. Freed from the burden of chick rearing, he has the energy to replace old feathers with new plumage. He aims to double his body mass in the days leading up to departure from the Maine coast. To accomplish such rapid weight gain, he doubles or triples the amount of food he eats. His stomach, liver, and intestines increase in size too. It is a temporary change, however. Blackpolls migrating over the ocean have no opportunity to eat. He sheds unnecessary mass at the same time he sequesters fat by shrinking the size of his gut and liver during last days before migration. In late September or early October when he alights on a spruce crown hugging a rocky headland, overlooking waves crashing beneath, the bird is ready.

I broke my run into five sections, each punctuated by a short break to drink water and eat food. I divided the warbler’s effort similarly in my mind, although he does not stop or ingest any food or water while migrating over the Atlantic Ocean. The five divisions of his migration are merely an arbitrary method to frame the comparison. He weighs anywhere from 20-23 grams upon departing Maine. His species’ over-ocean route averages 3,000 kilometers (1,864 miles). Radar observations of migrating songbirds have found a flight speed of 38 – 43 kilometers per hour. At a 40 kilometer per hour pace, the blackpoll will need 75 hours to arrive in Puerto Rico. If he decides to skip the Caribbean islands, he may fly non-stop for 88 hours. I aimed for a 5-hour, 42-kilometer (26.2-mile) run. It is not the same.

I felt ready for my run when I began on April 5, although I would also make mistakes along the way.

Mike’s Marathon. Section 1: 7.4 miles. Total distance: 7.4 miles.

I follow my short loop route from home plus a mile-long spur to increase the mileage on the first leg. I run a combination of town roads, logging roads, and ATV trails. The trails remain snow covered and a little squirrelly underfoot, but the snow is compacted and shallow enough that it isn’t a burden to run through. I feel fine at the end of the section, like this is just a warmup. Upon reaching home, I’m not very hungry or thirsty. Still, I fuel up with cookies, chocolate milk, and water knowing that I need the energy and liquids in my body later.

Blackpoll migration. Late September. Section 1. Total flight time: 21 hours. Total flight distance: 840 kilometers.

A passing cold front brings northerly winds. The blackpoll cannot be still. He expresses zugunruhe, a German word which means migratory restlessness. He relieves it at nightfall by launching over the Gulf of Maine. Challenges lay ahead, but he’s made for flying. Pneumatic bones offer reduced mass without compromising bone strength. His blood binds to and carries oxygen at higher affinities than mammals so he can better supply oxygen to flight muscles under challenging conditions. Importantly, the blackpoll breathes with an ease that I can’t match. Unlike my dead-end, mammalian lungs where inhaled air mixes with the previous breath, his respiratory system is unidirectional. He uses a system of air sacs to inhale and exhale. None of a bird’s nine air sacs contain blood vessels. They play no part in the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide. Birds have no diaphragm either, so the air sacs serve as bellows and air storage areas for the lungs in addition to connecting with hollow bones in their bodies. As the blackpoll inhales, half the incoming air fills one lung while the other half enters a pair of caudal air sacs. This breath also moves previously inhaled, deoxygenated air from the lungs to cranial air sacs. Exhalation pushes air from the lungs and the cranial sacs out through the trachea, while fresh air stored in the caudal air sacs moves behind the departing air into the lungs. The cycle ensures that his lungs always receive fresh, oxygenated air. It is an elegant, efficient system. I wish I had it. Despite his flight time and distance covered thus far, the bird still has 54 hours to go.

Mike’s Marathon continued. Section 2: 3.6 miles. Total distance: 11 miles.

I run to the east end of my road and back. The route undulates and this is no burden at this stage of the run. I remain energetic, although I am in no way pushing my pace beyond a comfortable level. It’d be hard to participate in a conversation as I run, but I’d have the breath to try. I eat and drink more upon returning home.

Blackpoll migration continued. Section 2. Total flight time: 31.5 hours. Total flight distance: 1,260 kilometers.

It is the second full day of his obligatory flight. The effort is directly tied to his survival. He cannot survive the cold temperatures of a North American winter. He could utilize an overland route to escape. Some blackpolls do, especially those in poorer body condition. Stopping frequently can reduce the risk of exhaustion, but it can also slow the pace of migration and increase the bird’s vulnerability to predators. One big leap over the ocean, so to speak, can save overall flight time and reduce the risk of predation. Natural selection has determined this is his best bet.

Mike’s marathon continued. Section 3: 5.4 miles. Total distance: 16.4 miles.

I run west from home to the end of the road and back. The road is straight and hilly. Navigating remains easy. I don’t even need to think about it, having run this way dozens of times previously. I only need to remember how far to go. I feel thirsty at the end of each section, yet I still pee about every hour. The cool weather helps reduce my body’s need for liquids. Between 25˚ and 35˚ F are the perfect temperatures for running, IMO, and that’s the weather provided today. Perhaps I should take better advantage of it. The original goal was a 20-mile training run, which the training book does not call for, after completing an 18-miler last week, yet my legs still feel good at the end of this section. I begin to believe I can finish the marathon if I commit to it. With the favorable weather and my body cooperating so far, I decide to get it over with.

Blackpoll migration continued. Section 3. Total flight time: 46.5 hours. Total flight distance: 1,860 km.

The bird has flown through another night. After dark, he becomes an astronomer by using the apparent rotation of the stars in the sky to determine direction. Has favorable weather eased the journey south or has it become a barrier to progress? Headwinds close to a bird’s flight speed can stall forward movement. Wind from the wrong direction can blow him off course or force him to use extra energy to stay on course. A tailwind, in contrast, would provide the extra push needed to get him over the last dangerous stretches of open sea. Is the blackpoll feeling different compared to when he started? Do his flight muscles ache? He’s been flying for two days, non-stop. A lack of sleep, surprisingly, isn’t an issue. Birds can sleep only one half of their brain at a time. Even when flying, they keep at least one eye open.

Mike’s marathon continued. Section 4: 4.6 miles. Total distance: 21 miles.

I go east again with a short detour off the main road to add an extra mile. I feel worked but not exhausted. The greatest discomfort exists at the bottom of my feet and toenails from the constant pounding of footfalls. I’m losing a toenail from a long run I completed a couple of weeks ago. I do not want to lose any more. I try to adjust my stride on the downhills to compensate. There is no flat section, however. Just false flats at best. I’m tired, but I also still think I can finish another five miles. At the end of this section, I eat and drink again. It won’t be enough as I’ll soon discover.

Blackpoll migration continued. Section 4. Total flight time: 60 hours. Total flight distance: 2,400 km.

The ocean and clouds do not provide reliable landmarks to aid his navigation. He’s not flying blind, though. Unlike me, the blackpoll does not rely on landmarks to follow his migratory route. Cells in his upper bill contain magnetite. Scientists theorize this allows the bird to sense the strength of the magnetic field. His retina includes special light gathering cells, known as a cryptochromes. Light at the blue and turquoise end of the spectrum excites electrons within the cryptochromes, which may allow the bird to actually see direction. It would be a stunning ability to possess. The blackpoll has flown far enough that he might be able to land on a Caribbean island if necessary. He could also choose to keep going to the north coast of South America. Do hunger and energy levels make the decision for him?

Mike’s marathon finale. Section 5: 5.4 miles. Total distance: 26.4 miles. Destination: Home.

The first few miles of the last section are tolerable. I’ve slowed considerably since the start of the run more than four hours ago, but at least my energy hasn’t bottomed out. Until it does. About three miles from home and my finish line, I feel gassed. Runners call it hitting the wall. Cyclists call it bonking or blown-out legs. No matter what, it sucked. I should’ve consumed more fuel at my last pit stop. I could use that energy now and I regret not carrying some snacks with me for the final leg. The bottom of my feet ache. Each trot is an effort. I am a little light-headed. There is a weird tingling sensation from my elbows to my fingertips. But the only choice is to move forward. Stopping would be worse. There’s little chance of hitching a ride if I quit. I see two cars in the last hour of running. I can’t remember if I needed to run all the way to the end of the road but do anyway so I don’t end up short of a full marathon when I get home. In between thoughts of food and water, with no alternative transportation other than my legs and feet, I set mini goals. Get to the next knoll. Get to the base of that hill. Get to that dirt road a few hundred yards ahead. Be glad you’re not at the start of the race. The last half of the marathon was harder than the first. The last five miles was harder than the previous five miles. The last three miles was harder still. The last mile was hardest of all. Cresting the last rise in the road, I can see the house. Near exhaustion becomes relief.

Blackpoll migration finale. Section 5. Total flight time: 75 hours. Total distance: 3,000 km. Destination: Puerto Rico.

My energy tanked when I failed to eat during the last five miles of my marathon. The blackpoll hasn’t eaten any food or drank any water since leaving Maine three days ago. Fat has been his primary fuel. The warbler used special enzymes to better mobilize stored body fat, specialized transporter proteins to carry fat through the bloodstream, and additional special enzymes to get fats into muscle cells and deliver it to the cells’ mitochondria. Burning fat also produces metabolic water, just enough hydration to keep him going. The blackpoll’s abdomen bulged with fat upon departure three days ago when he weighed about 20 grams. He now weighs about 13 grams. The effort cost him one-third of his body mass. He’s nearly emaciated as he reaches Puerto Rico. He’ll stay here for a few days to refuel before continuing to South America. He needed all his physiological and metabolic tricks to make the journey successfully. Does he also feel an avian equivalent of relief when sighting his final destination?

Running a marathon and then comparing it to the blackpoll’s migration has been humbling. I’m glad I finished the marathon, although I’m still not sure why I did it. Maybe I ran it just for the challenge, which I suppose is as good of a reason as any. The blackpoll, in contrast, migrates because instinct compels him. Nevertheless, my marathon was in no way equivalent to the blackpoll’s fall migration. I didn’t gain any immediate reproductive or survival benefits. The blackpoll did. I didn’t have to worry about drowning in the ocean if I stopped. The blackpoll did. I didn’t have to evade predators waiting to take advantage of my exhaustion upon arrival. The blackpoll did. I didn’t move non-stop for three days. The blackpoll did. I didn’t have to forage for wild foods when I finished. The blackpoll did. I don’t have to repeat the journey next year. The blackpoll does, all the while achieving feats of endurance no human can replicate.

References:

- DeLuca, W. V, et al. (2015) Transoceanic migration by a 12 g songbird. Biology Letters. 11(4): 20141045. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2014.1045.

- DeLuca, W., et al. (2020) Blackpoll Warbler (Setophaga striata), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.bkpwar.01.

- Lovette, I. J. and J. W. Fitzpatrick, eds. (2016) Cornell Lab of Ornithology Handbook of Bird Biology. Third Edition. Princeton University Press.