Dry weather has been infrequent in western Washington this fall, so when a clear day dawned earlier this week I couldn’t resist the opportunity to take a wandering bike ride, one of my favorite pastimes. Over the last several years, my bicycle rides and hikes have become far more leisurely since I have become more prone to distraction. Without a fixed agenda though, I’m more open to discovery. Why, for example, would anyone pass on the chance to see a baby snake?

This tiny garter snake was basking on the side of the road on a warm fall day in late October. Concerned it might become road kill, I moved it off of the pavement.

With temperatures near freezing on Monday, I wasn’t going to find any snakes, but over a fifty mile round trip—from Skagit River to the end of the road near Baker Lake—I found more than enough to hold my attention. After a mere two miles of pedaling, I found a reason to pause.

I began at the old concrete silos in Concrete, a small town along the middle reaches of Skagit River…

Why was Concrete named Concrete? You only get one guess.

No, I didn’t ride the hill as slowly as Google Maps says it will take.

…and immediately began a steep climb up Burpee Hill. In two miles, the road gains over 800 feet of elevation, although I didn’t mind the opportunity to warm up with frost lingering on the grass.

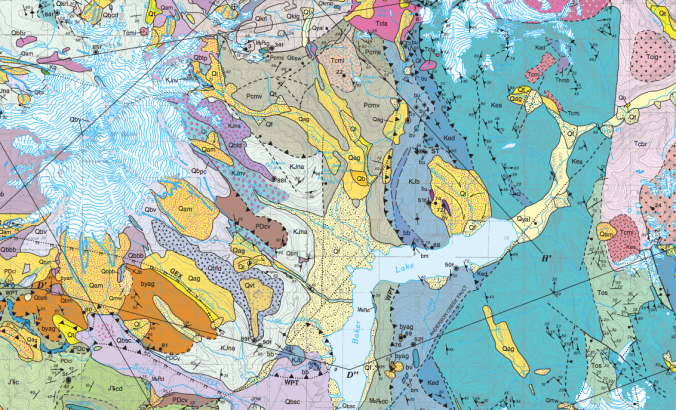

The North Cascades region is the sum of a complex geologic history. Large-scale mountain building, volcanism, and extensive glaciation created and shaped a landscape of unparalleled ruggedness in the Lower 48 states. This area’s geology is, well, complicated. Just take a look at the geologic map.

Yikes.

On a bicycle, unlike in a car, stopping to check out roadside curiosities—wildlife, road kill, trees, wildflowers, rocks, scenery—is very easy and is an important reason why I enjoy it so much. About half way up the Burpee Hill climb, I stopped to ponder some interesting sediments exposed in a road cut. The coarse to fine grained sediments were well sorted, indicating flowing water had deposited them, and were capped by a mix of unsorted rocks. This is one piece of a grander glacial puzzle.

A few exposures of loose and coarse sediment can be found on the Burpee Hill Road.

Maps that outline the last glacial maximum in North America give the impression that ice flowed largely north to south. While generally true, the story is a bit more complex on a local scale, as Burpee Hill illustrates.

Glaciers are masses of ice that flow and deform, and they behave differently than ice from your freezer. Set an ice cube on a table and strike it with a hammer and it will fracture. Ice in a glacier’s interior, however, is under tremendous pressure. Ice crystals are altered and deformed like plastic putty, so much so that only the upper 30 meters of temperate glaciers are brittle. (The relatively consistent maximum depth of crevasses reveals this fact. Below 30 meters, deforming ice seals any crevasses. Cavities at the base of glaciers have been measured to seal as fast as 25 centimeters per day.) The ice is not impervious to liquid water though. Within temperate glaciers, ice remains at or slightly above freezing, which allows meltwater to percolate to the glacier’s base. Pressure from overlying ice also causes some water to melt at the bed. Once there, meltwater acts as a lubricant helping the glacier slide. These factors, combined with gravity’s pull, drive glaciers along the paths of least resistance, and sometimes these paths lead uphill.

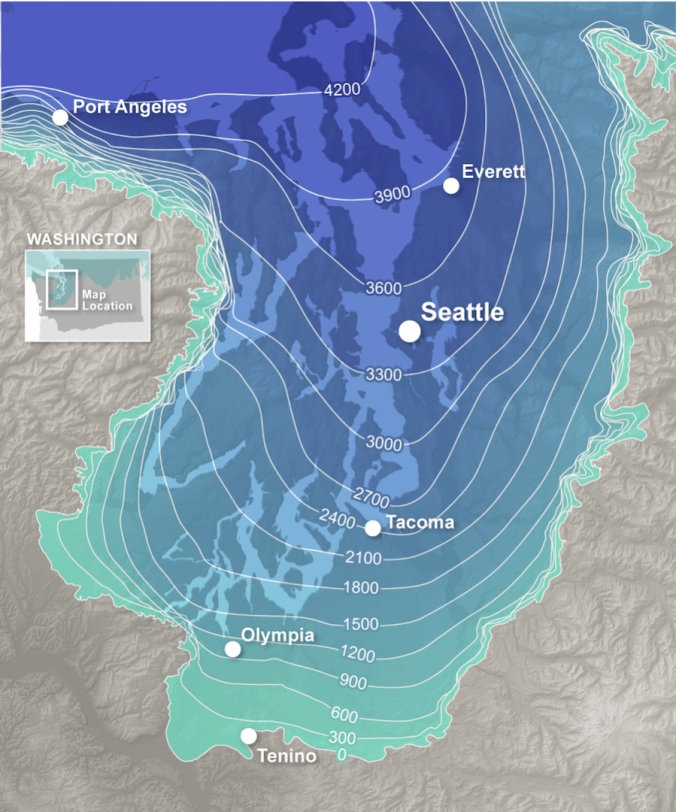

Between 19,000 and 18,000 years ago, a broad lobe of the cordilleran ice sheet invaded the lowlands of Puget Sound. Fingers of the ice sheet reached into the North Cascades as it continued to advance southward. Around 16,000 years ago, the ice sheet reached its maximum extent in western Washington, reaching south beyond Seattle, Tacoma, and Olympia.

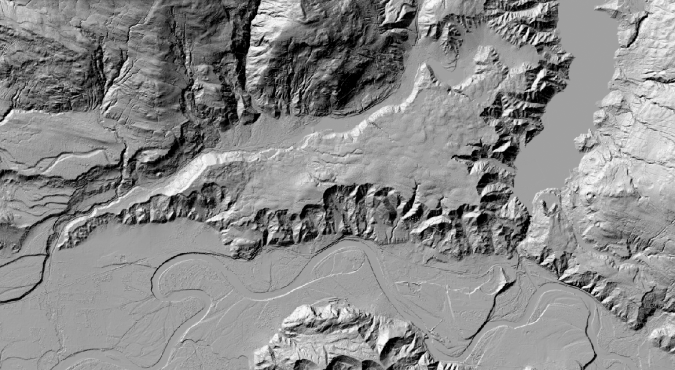

On the margin of the ice sheet, lowland valleys like the Skagit offered ice easy passage as it advanced. About 18,000 years ago in the lower and middle reaches of the Skagit valley, ice flowed in the opposite direction of the modern Skagit River. Burpee Hill is largely the result of this process. It’s a 200 meter-thick layer of glacial outwash, glacial lake sediments, and glacial till deposited at the front of ice as it advanced up the Skagit valley. The features are clearer in a LIDAR image.

Burpee Hill is the wedge-shaped feature in the center of the image.

Glacial ice from the Puget Sound area flowed east over the current location of Concrete. The sediments that make Burpee Hill were deposited in front of the advancing ice.

Since its formation, erosion and landslides have eaten away at Burpee Hill, and it is easy to overlook when the lure of craggy peaks and snow-capped volcanoes always dangles ahead. If volcanoes and orogenies are architects of this landscape, then glaciers are certainly its sculptor, reshaping landforms in profound ways. Stories like this are tucked away everywhere. Landforms are rarely ordinary.

Epilogue:

I continued my ride, which (in case you’re wondering) was wonderful even though temperatures remained near freezing. As I expected it to be on week day in early December, the road was quiet. The views of Mount Baker, pockets of old growth forest, and Baker Lake were worth the effort.

What a nice way to spend a day, Mike. Thanks for sharing the scenery and the science.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Mike,Very interesting post; always enjoy your musings. Miss you so much from bear cams. Sincerely,Barbara

LikeLike

Enlightening, Mike. I am thinking that the creation of new ice and landscapes is happening today in the Artic and in fact all around the world. And, so it is.

LikeLike

TY Mike for a beautiful trip down memory lane for me. We enjoyed our trips through Washington state on many occasions – never bike riding though – just thru car windows. The Northwest is amazing so very much to take in and appreciate. I would imagine with all the pedaling you did on a frosty day you maintained lots of body heat. Usually I don’t like snakes but am very familiar with the little buddy you met on the road – glad he didn’t join the numbers of road kill.

LikeLike

Thank you for the ride! 🙂

LikeLike

Thanks Mike. I was hoping you would take us along on some more of your bike rides.

And ‘yikes’ indeed. That is some crazy geology. I did not realize that Puget Sound was partially carved by glaciers, but it makes sense.

LikeLike

I used to live in concrete. And it is beautiful country!! I’m curious how many breaks u had to take riding ur bicycle up burpee. That guy is really steep. I’ve seen people who have come down in there cars and their brakes are smoking when they pull into to gas station at the bottom of the hill. And the surrounding area is also awesome.

LikeLike

Yeah, the Skagit Valley is a wonderful area. I’ll admit to taking breaks on that hill, although it really depended on my motivation. When I was checking out the geology I’d make a few different stops, but if I wanted to ride to Baker Lake then I’d usually just push through to get to the top. The ride down was always so fast, and a little treacherous. (A toast to good working breaks on my bike!)

LikeLike